Cold Male

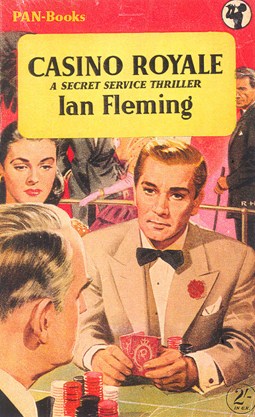

This essay on Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale was first published in Issue 1 of KKBB magazine in Autumn 2005, in advance of the 2006 film adaptation starring Daniel Craig. I have also written about the novel and the various attempts to film it in Rogue Royale, which can be read on this website or downloaded as part of the free ebook Need to Know.

‘The one with the carpet-beater.’ For too long, Casino Royale has been defined by one (admittedly brilliant) scene. The novel’s place in the canon of espionage fiction is assured by simple virtue of it being the first novel to feature James Bond, but apart from the infamous torturing of its hero, it is rarely given any serious analysis. This is a shame, because although it was not as commercially or critically successful as Fleming’s subsequent novels, there’s a strong case to be made for it being the first great spy thriller of the Cold War.

That the case hasn’t been made is probably due to several factors. Most obviously, many elements of the book don’t easily fit the genre: the setting is not Berlin or Budapest, but a small seaside resort in northern France, and the plot involves gambling for high stakes in a casino rather than stealing documents or smuggling a defector across a border. With its champagne and caviar, casino chips and cocktail dresses, it sometimes seems more like an F Scott Fitzgerald story than a spy novel.

But it is a spy novel—Fleming marks it out as such in the first chapter, ‘The Secret Agent’, in which James Bond practises some fairly nifty pieces of tradecraft. He doesn’t take the lift up to his hotel room, because it would warn anyone on that floor someone was coming. And, once he has established that no one is in the room, he checks that his traps have not been disturbed: a strand of hair wedged into a drawer in the writing desk, a trace of talcum powder on the handle of the wardrobe, and the level of water in the lavatory cistern.

Bond is in Royale-les-Eaux—a fictionalised counterpart of Deauville—on a mission to bring down the mysterious Le Chiffre, who M.I.6.’s report describes as ‘one of the Opposition’s chief agents in France, and undercover Paymaster of the “Syndicat des Ouvriers d’Alsace”, the Communist-controlled trade union in the heavy and transport industries in Alsace, and as we know, an important fifth column in the event of war with Redland’.¹

Le Chiffre is in trouble, although he’s unaware just how much. SMERSH, ‘the most powerful and feared organisation in the U.S.S.R.’² knows that he has embezzled some 50 million francs of party funds, which he has lost in the prostitution racket. Le Chiffre’s scheme to extricate himself from this mess—to win the money back at baccarat—is utterly implausible, and M.I.6.’s idea to send an agent out to France to make sure he loses even more so. But, in a trick that Fleming was to make his trademark, we don’t dwell on the absurdity, because it’s surrounded by such a wealth of verisimilitude. SMERSH was a real organisation, now best known (outside the Bond novels) for having hunted down suspected traitors to the Soviet Union in the months following the Second World War.³

Fleming used his own experiences and knowledge of espionage throughout the novel, and even the most sensational elements are grounded in reality. In Chapter Nine, Bond tells Vesper that he earned his Double O prefix by killing a Japanese cipher expert in New York and a Norwegian double agent in Stockholm. In 1941, Fleming had visited the New York offices of the M.I.6. offshoot the British Security Coordination (B.S.C.). He was shown around the headquarters by the organisation’s ‘M’, Sir William Stephenson (the famous ‘Intrepid’), and witnessed the burglary of an office belonging to a cipher expert working in the Japanese consul on the floor below.⁴ According to one former B.S.C. officer, the B.S.C. did carry out at least one assassination in New York during the war.⁵ Bond’s mission to bankrupt Le Chiffre was inspired by another of Fleming’s wartime experiences, when he attempted to take on some German agents he had recognised in the casino in Estoril in Portugal—unlike Bond, though, Fleming lost.⁶

Note, too, that Le Chiffre is not just an agent of an opposing power, but of ‘The Opposition’. In 1952, when Fleming started writing Casino Royale, the Cold War was entering its seventh year—it started in the closing stages of the Second World War. M.I.6.’s report refers to ‘the event of war with Redland’. This is no thriller hyperbole—it was a very real fear in British military and intelligence circles at the time. Just five days after the Nazis’ surrender in 1945, Winston Churchill was considering a study drawn up by his Joint Planning Staff for a war against Russia. The date for the start of the Third World War was pencilled in for July 1, 1945.⁷ Although Churchill’s chiefs of staff rejected the idea, the feeling that the Cold War with the Soviet Union may at any moment turn hot was common during the 1950s.

But the most significant espionage element in Casino Royale is that of betrayal. A year before Fleming sat down to write the novel, the British diplomats Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean vanished. Although it was not publicly confirmed that they had been Russian agents until their appearance in Moscow in 1956, there was widespread speculation that this was the case, and Fleming, with his intelligence contacts, would likely have been better informed than most about M.I.6.’s attempts to track down the remaining members of the ‘Cambridge Ring’. Vesper Lynd represents the shadow of treachery that would haunt British intelligence for the next two decades. It also haunted British spy fiction: scores of thrillers in the ’60s and ’70s focussed on the hunt for a ‘mole’ in M.I.6. Casino Royale got there first.

That said, the novel has its own weight of influences. It is, of course, impossible to know all the books Fleming read and what he thought of them, but we can piece together some of it. It is often said that Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond was one of the primary models for Bond, but an interview Fleming gave to Playboy shortly before his death refutes that:

‘I wanted my hero to be entirely an anonymous instrument and to let the action of the book carry him along. I didn't believe in the heroic Bulldog Drummond types. I mean, rather, I didn't believe they could any longer exist in literature. I wanted this man more or less to follow the pattern of Raymond Chandler's or Dashiell Hammett's heroes—believable people, believable heroes.’⁸

The final phrase, ‘believable heroes’, is Casino Royale’s real innovation. Prior to its publication, there had been plenty of unbelievable heroes in spy fiction, and plenty of spy thrillers featuring believable characters – but they hadn’t been heroes. By merging the existing two schools of spy fiction, the heroic and the believable, Fleming forged an entirely new kind of spy thriller.

Beyond its innovation in the genre, beyond its unerring prose style, it is a novel about what it takes to be a man

The ‘believable’ school had been born in 1928, with W Somerset Maugham’s collection of short stories about the British writer-turned-agent Ashenden. This was the first piece of fiction to present espionage as a sordid and shabby line of work: until then, its depictions had been closer to propaganda (and in many cases were used as such). Ashenden is sceptical of the spying game from the start, when a colonel in British intelligence known only as R. tells him a story about a French minister who was seduced by a stranger in Nice, and lost a case full of important documents in the process:

‘“They had one or two drinks up in his room, and his theory is that when his back was turned the woman slipped a drug into his glass.”

Ashenden laconically notes that such events have been enacted in a thousand novels and plays: ‘“Do you mean to say that life has only just caught up with us?”’ R. insists that the incident happened just a couple of weeks previously.

‘“Well, sir, if you can’t do better than that in the Secret Service,” sighed Ashenden. “I’m afraid that as a source of inspiration to the writer of fiction it’s a washout. We really can’t write that story much longer.”’⁹

Writers did continue to create variations of the story, of course, and Casino Royale is one of them. With the Ashenden stories, Maugham changed the rules of earlier thrillers—works by the likes of William Le Queux and E. Phillips Oppenheim, whose romantic tales of derring-do had been best-sellers in the run up to the First World War. Both writers were fond of aristocratic heroes with refined tastes who saved England, usually from German plans to invade.

*

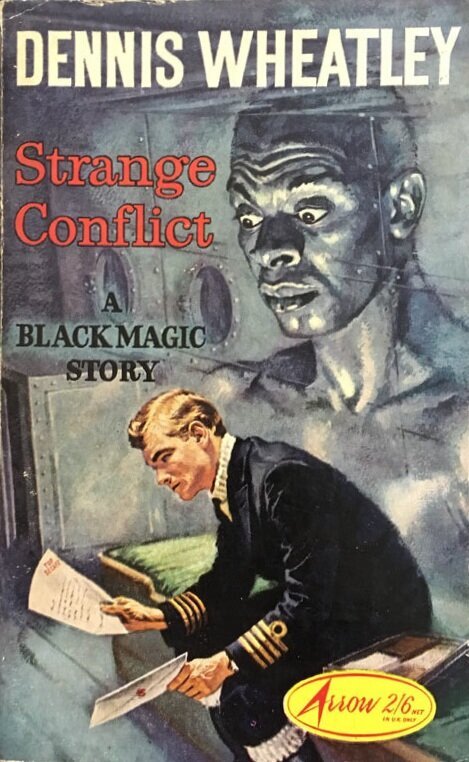

Another master of the heroic vein was John Buchan, author of The Thirty-Nine Steps, although his heroes were not usually professional spies, but gentlemen adventurers thrown in at the deep end. More relevant to Fleming, and Casino Royale in particular, is Dennis Wheatley, who wrote a string of Buchan-esque thrillers from 1933 until his death in 1977.

Wheatley, like Fleming, worked in intelligence during the Second World War, and had a fondness for the bizarre: as well as spy thrillers, he also wrote occult novels, and even merged the two genres in Strange Conflict (1941), which one can easily imagine a younger Fleming eating up. It features a privileged group of British and American agents trying to discover how the Nazis are predicting the routes of the Atlantic convoys. The trail leads to Haiti, but before the group even arrive on the island they are attacked by sharks. They are saved by a Panama-hatted Haitian called Doctor Saturday, who puts them up at his house and then takes them to a voodoo ceremony, where they witness a sacrifice to Dambala. Two women wearing black are shooed away by the priest; one of the group of agents asks Doctor Saturday why:

‘He replied in his broken French that they were in mourning and therefore had no right to attend a Dambala ceremony, which was for the living. Their association with recent death caused them to carry with them, wherever they went, the presence of the dreaded Baron Samedi.

“Lord Saturday,” whispered Marie Lou to the Duke. “What a queer name for a god!” But the Doctor had caught what she had said and turned to smile at her.

“It is another name that they use for Baron Cimeterre. You see, his Holy Day is Saturday. And it is a sort of joke, of which the people never get tired, that my name, too, is Saturday.”’¹⁰

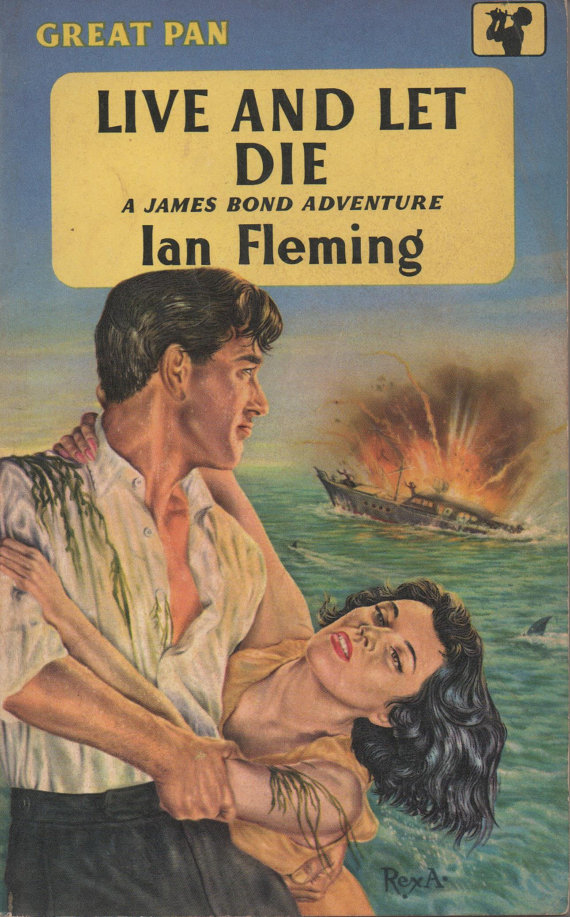

It is, of course, not a joke at all: Doctor Saturday, they soon discover, is the physical incarnation of Baron Samedi, and the villain they have been trying to track down. In Live and Let Die, published in 1954, Ian Fleming featured a villain with the same name transplanted to Jamaica, where he wrote all his books.

*

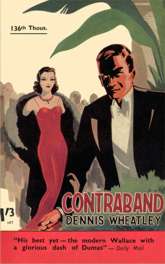

All of Wheatley’s work is now out of print, perhaps partly as a result of the sometimes virulent racism in his work. But leaving aside his politics, Wheatley was a considerable thriller writer—his chapters came thick and fast and almost always ended with ingenious cliff-hangers. He was also very successful: by the time Fleming sat down to write Casino Royale, Wheatley had over 20 best-sellers to his name, seven of them featuring a dashing British secret agent called Gregory Sallust, who travelled around the world stopping plots against England. This kind of character was very common throughout the 40s and 50s: in the 1951 novel The Sixth Column by Ian Fleming’s brother Peter, one of the characters is a retired army officer who makes a living writing thrillers featuring a Colonel Hackforth, who becomes involved in ‘violent and, to say the least of it, curious events’ that have ‘far-reaching implications’¹¹. But the similarities between James Bond and Wheatley’s character Gregory Sallust are more striking. Both are lean, dark, handsome, ruthless and high-living. In Contraband (1936), we meet Sallust gambling at the casino in Deauville, ten days before la grande semaine. The first chapter, “Midnight at the Casino”, finds Sallust attracted by a girl at one of the tables:

‘Probably most of the heavy bracelets that loaded down her white arms were fake, but you cannot fake clothes as you can diamonds, and he knew that those simple lines of rich material which rose to cup her well-formed breasts had cost a pretty penny. Besides, she was very beautiful.

A little frown of annoyance wrinkled his forehead, catching at the scar which lifted his left eyebrow until his face took on an almost satanic look. What a pity, he thought, that he was returning to England the following day.’¹²

Casino Royale, of course, opens in the same casino three hours later. And in Chapter 8, Fleming describes Vesper Lynd in very similar terms:

‘Her dress was of black velvet, simple and yet with the touch of splendour that only half a dozen couturiers in the world can achieve. There was a thin necklace of diamonds at her throat and a diamond clip in the low vee which just exposed the jutting swell of her breasts. She carried a plain black evening bag, a flat oblong which she now held, her arm akimbo, at her waist. Her jet-black hair hung straight and simply to the final inward curl below the chin.

She looked quite superb and Bond’s heart lifted.’

The woman in Contraband is a Hungarian called Sabine Szenty, and she turns out to be part of a smuggling gang. We learn that she has ‘sleek black hair’, a ‘fresh and healthy’ complexion, and wears ‘light make-up’¹³. In Chapter 5 of Casino Royale, we are told that Vesper is ‘lightly suntanned’ and wears no make-up, except on her mouth. Bond and Sallust are also similar, in that they are both attracted to richness that is both understated and simple. This is a repeated theme in Casino Royale:

‘He dried himself and dressed in a white shirt and dark blue slacks. He hoped that she would be dressed as simply and he was pleased when, without knocking, she appeared in the doorway wearing a blue linen shirt which had faded to the colour of her eyes and a dark red skirt in pleated cotton.’¹⁴

Sallust also has a familiar hedonistic streak. During the course of Contraband, he quaffs champagne, eats duck dressed with foie gras and cherries, and is briefly held captive in a country house in Kent—although he escapes before he is dumped in a nearby river. He also narrowly avoids drowning in V For Vengeance (1942), and as a large Prussian holds his head under water he grows contemplative:

‘The game was up. He would never again know the joy of Erika’s caresses, the thrill of a new adventure, the feel of a hot bath and a comfortable bed after a long hard journey, or the cool richness of a beaker of iced champagne...’¹⁵

In Casino Royale, James Bond luxuriates in just this kind of activity, although he prefers cold showers to hot baths—he has four of them in the course of the book.

*

All of this is a long way from the ‘believable’ image of espionage depicted by Maugham and his successors, Eric Ambler and Graham Greene, none of whose protagonists could rightly be called heroes, and who are more likely to think of their collection of rare stamps than beakers of champagne. And yet Casino Royale's prose style is far closer to the believable school than it is to Buchan and Wheatley, whose writing tends to be flat and heavy-handed. In a letter to Fleming in 1953, Maugham wrote that he had enjoyed the novel immensely, in particular the baccarat battle between Le Chiffre and Bond.¹⁶ Before Bond, there were dozens of thrillers featuring debonair spies who win the day—Casino Royale was the first that was written with real flair. Wheatley, Buchan and the others could keep you reading—Fleming keeps you re-reading.

But he wasn’t the first to try the trick of merging these two styles. From 1936, Geoffrey Household wrote several vividly written thrillers that added a dose of toughness and realism to the Buchan model. Fleming was a great admirer of Household—we know he sent at least six copies of his 1937 novel The Third Hour to friends even though Household would not become famous until two years later, with the publication of the classic Rogue Male.¹⁷

It’s not hard to see the appeal: Household had served in the Intelligence Corps in the Middle East during the Second World War, and shared much of Fleming’s outlook on life. His books are almost all in the first person, and his heroes tend to be laconic, arrogant and ruthless. In A Time To Kill (1951), the narrator is desperate to save his family, who have been kidnapped by communist agents:

‘I gave him Pink’s knife between the shoulder blades. It wasn’t quite enough. I am now ashamed that I was glad it wasn’t enough. I turned him over and allowed him to see who I was, and to watch the steel as I drove it into his throat.’¹⁸

Rogue Male, published a few months before the outbreak of the Second World War, features an upper-class Englishman and amateur hunter who decides on his own initiative to assassinate Hitler. When his shot misses, he is chased across the Channel by a German agent masquerading as a British officer called Quive-Smith, and a tense cat-and-mouse tale plays out in the English countryside. To keep off the streets, the narrator burrows himself an ingenious bolt-hole, but this backfires when Quive-Smith finds him and fills the hole in—like Bond in Casino Royale, the narrator finds himself at the mercy of a foreign agent. While he is trapped, Quive-Smith tries to get him to admit that he was acting as an agent of the British government; the narrator insists he was not, which irritates Quive-Smith’s sense of order:

‘“Shall we say that your motives were patriotic?”

“They were not,” I answered.

“My dear fellow!” he protested. “But they were certainly not personal!”

Not personal! But what else could they be? He had made me see myself. No man would do what I did unless he were cold-drawn by grief and rage, consecrated by his own anger to do justice where no other hand could reach.’¹⁹

The narrator’s denial that he has acted out of patriotism immediately sets this book apart from the romantic tradition—and yet his ‘cold-drawn grief and rage’ is painted in a heroic light. In Casino Royale, Fleming took this idea a step further. The word ‘cold’ is repeatedly used to describe Bond in the book’s early stages—at the end of the first chapter, he is depicted almost as a villain:

‘Then he slept, and with the warmth and humour of his eyes extinguished, his features relapsed into a taciturn mask, ironical, brutal, and cold.’

As we have already seen from the description of Gregory Sallust in Contraband, this is not entirely out of keeping with the romantic tradition—but it is still quite extreme. A turning point comes at the end of Chapter 13, when Bond’s mask is finally removed. He has beaten Le Chiffre at baccarat and apparently completed his mission, but his celebratory dinner with Vesper has turned sour. He returns to his hotel room to hide the cheque and bed down for the night:

‘He gazed for a moment into the mirror and wondered about Vesper’s morals. He wanted her cold and arrogant body. He wanted to see tears and desire in her remote blue eyes and to take the ropes of her black hair in his hands and bend her long body back under his. Bond’s eyes narrowed and his face in the mirror looked back at him with hunger.’

Bond is frustrated because he seems to have met his match—a woman more detached than him. Despite the previous references to Bond’s coldness, this passage is shocking in its intensity and aggression towards Vesper. Although it is brutal, even sadistic, it is no longer ironical or cold in the sense of being detached—Bond’s emotions have finally risen to the surface.

When, in the novel’s final chapter, Bond learns of Vesper’s betrayal, he utters an obscenity, cries, and then ‘with a set cold face’ walks to the nearest telephone booth and calls London to inform them that ‘the bitch is dead now’. Grief has turned to rage in a few short sentences, and the rage is then turned away from Vesper and directed at SMERSH.

‘SMERSH was the spur. Be faithful, spy well, or you die. Inevitably and without question, you will be hunted down and killed.

It was the same with the whole Russian machine. Fear was the impulse. For them it was always safer to advance than retreat. Advance against the enemy and the bullet might miss you. Retreat, evade, betray, and the bullet would never miss.

But now he would attack the arm that held the whip and the gun. The business of espionage could be left to the white-collar boys. They could spy, and catch the spies. He would go after the threat behind the spies, the threat that made them spy.’

Like the narrator of Rogue Male, James Bond vows ‘to do justice where no other hand can reach’. Things have become very personal for the cool, detached agent. In the course of his mission, he has proved, quite literally, that he has the balls for the job. The glamour of the casino and the champagne and caviar have been stripped away, and we are left with one man battling his own private nightmare.

And this, perhaps, is why Casino Royale still resonates today. Beyond its innovation in the genre, beyond its unerring prose style, it is a novel about what it takes to be a man. How to be a man in the best of circumstances—when you are in your prime, a beautiful woman by your side, winning against the odds—and how to be a man in the worst of circumstances, when you are under pressure and can’t let the side down, and the woman turns out to have betrayed you. Before Casino Royale, the hero always saved the damsel in distress moments before she was brutally ravaged and tortured by the villain; Fleming gave us a story in which nobody is saved, and it is the hero who is abused, drawn there by the damsel. Despite the implausibility of his mission and the sometimes self-consciously crude depiction of a tough man of action, in Casino Royale Fleming succeeded in creating his believable hero.

This may be another reason the novel has been so neglected by scholars of the thriller. Although it established the formula for the series, Casino Royale has a very different tone to the rest of the Bond novels. For decades, critics have painted Bond as an unbelievable hero in the Sapper or Buchan tradition but, as I hope I’ve shown, in Casino Royale he is not quite of that mould.

As Fleming’s subsequent novels and the films made James Bond the most famous secret agent in the world, other writers—John Le Carré, Len Deighton, Adam Hall—produced more ‘believable’ stories than Casino Royale. These were often acclaimed as being ‘anti-Bonds’, but in fact they followed Fleming’s lead in weaving heroic elements into the Maugham/Ambler/Greene tradition. Deighton’s The IPCRESS File (1962) and Hall’s The Quiller Memorandum (1965) were both regarded as more credible accounts of espionage than Fleming’s novels, and yet they both feature torture scenes that, consciously or not, owe a great debt to Casino Royale. With Fleming’s first novel, the spy thriller took an enormous leap forward.