PART ONE

When Ian Fleming sat down at his desk in Jamaica in early 1952 to write his first novel, one of the most significant decisions he made was naming his protagonist, as he explained in 1961:

‘I was determined that my secret agent should be as anonymous a personality as possible, even his name should be the very reverse of the kind of “Peregrine Carruthers” whom one meets in this type of fiction.’[1]

He said something similar in an interview with the BBC in April 1962:

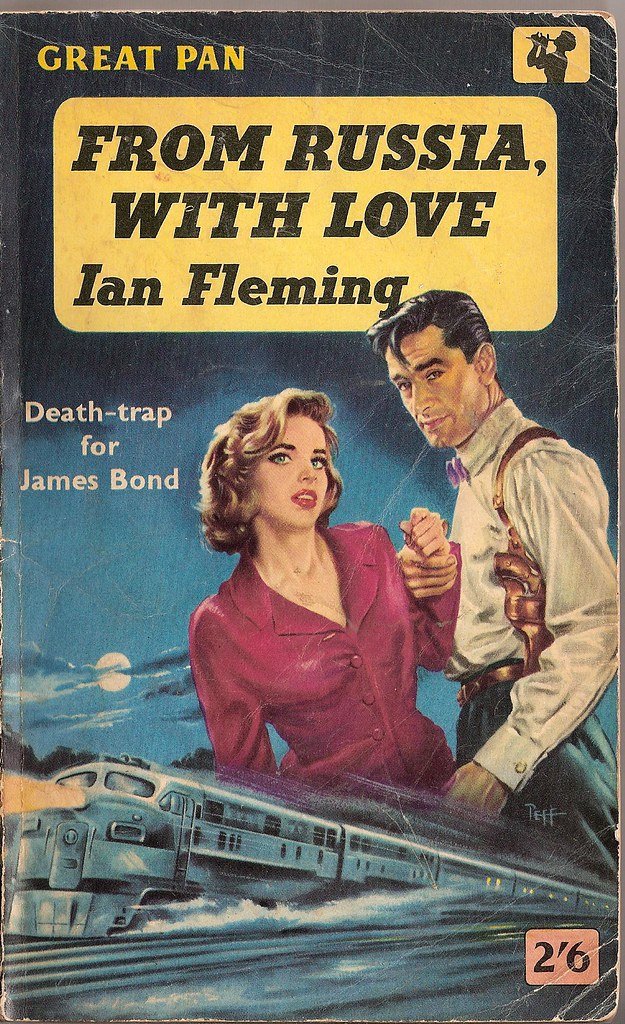

‘When I first thought of him as a character I intended him to be purely a blunt instrument in the hands of his government, who would be subjected to various adventures and excitements, but who would not show up as the stock hero of, for instance, let’s say the Buchan books or Bulldog Drummond, and so on and so forth, or the Saint, where the man is definitely given a heroic role. I meant this man really to be an extremely capable instrument in the hands of the government, and that is one of the reasons why I gave him such an extremely dull name, because rather than call him, for instance, Peregrine Carruthers, or something of that sort, I called him James Bond, being to my mind the dullest name I could lay my hands on.’[2]

And again when interviewed for Canadian television in February 1964:

‘I wanted to find a name which wouldn’t have any of the romantic overtones, like Peregrine Carruthers or whoever it might be. I wanted a really flat, quiet name.’[3]

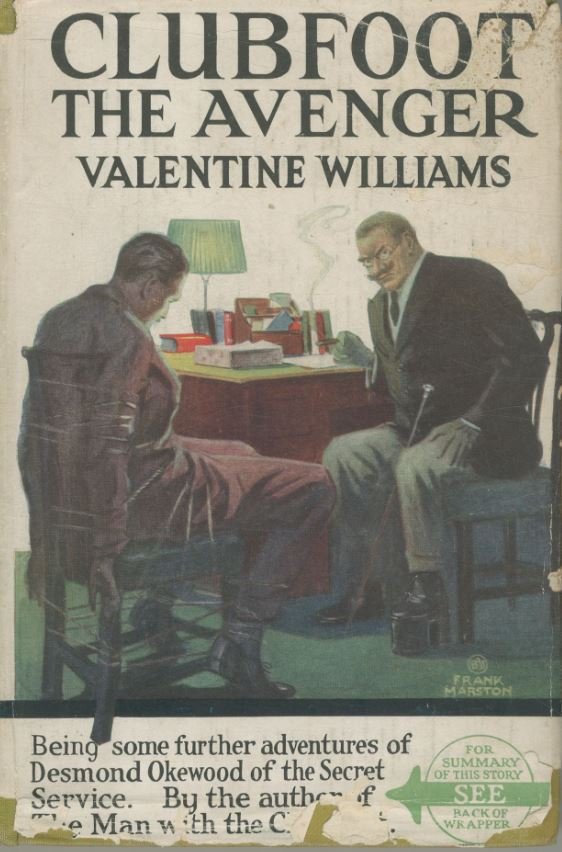

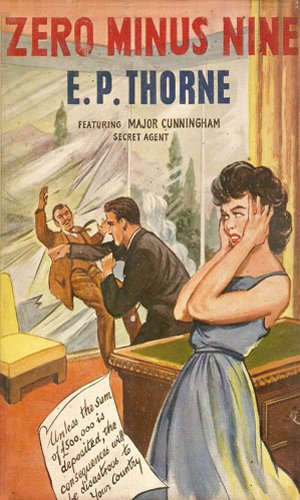

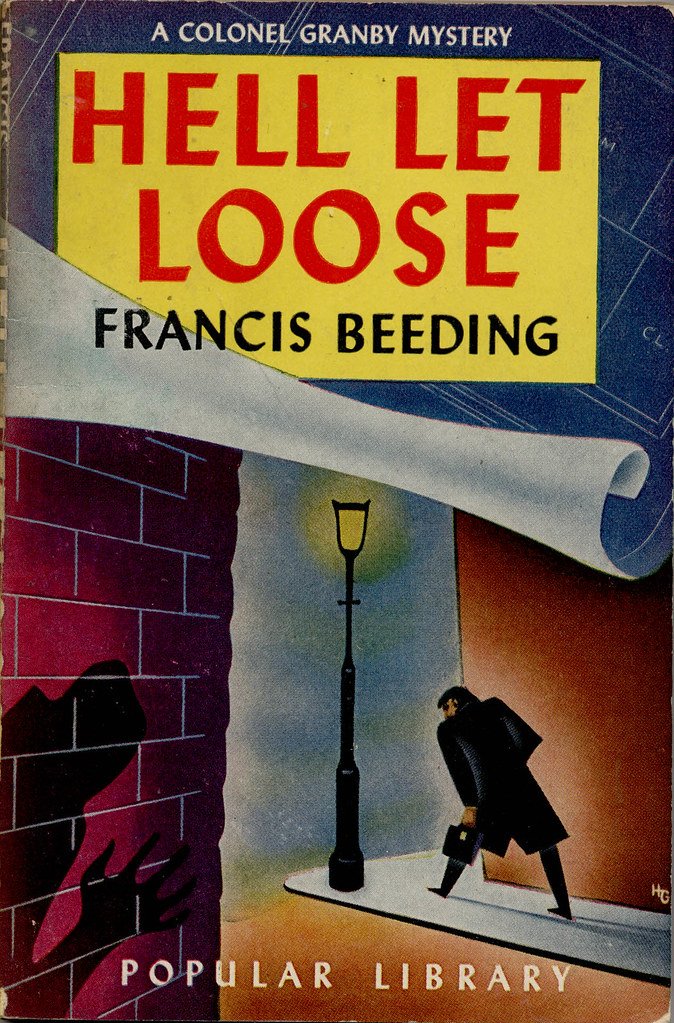

There had been straightforward names for heroes in the British thriller before – Richard Hannay, Simon Templar – but the genre was also populated by characters with extravagant names and nicknames, often polysyllabic and sounding upper-class: Desmond Okewood, Swithin Destime, Denis Nayland Smith, Colonel Alistair Granby, Major ‘Brains’ Cunningham[4]. Fleming realised that this device had run its course; as very few people in real life had such names, it was a barrier to believing in characters with them. The difference in impression given by reading about a secret agent called James Bond and one called ‘Brains’ Cunningham is significant: even if many of the particulars of the characters are similar, ‘Bond’ immediately sounds more credible, modern, grown-up and, indeed, capable.[5]

But Peregrine Carruthers, the name Fleming chose for his ‘counter-Bond’ figure, is also interesting. Carruthers is a Scottish surname but, as with Peregrine, is most often used in fiction to denote someone English and upper-class. However, fictional Carrutherses tend to be pompous politicians, officious diplomats, stern doctors, and the like, and are usually minor characters rather than protagonists [6]. An exception is the narrator of Erskine Childers’ 1903 novel The Riddle of the Sands, a bored Foreign Office official who is drawn into intrigue by an invitation from Arthur Davies, an old acquaintance from his days as a student at Oxford, to go sailing in the Baltic [7]. Fleming might have had this in mind. Writing in 1955, he suggested that the novel would always be read due to its ‘beautifully sustained atmosphere’ and called Childers ‘one of the father-figures of the thriller’, although he was highly critical of the book as a whole. Other than its atmosphere, he felt the opening scenes were its main strength:

‘Shall you go with Carruthers to Cowes or accompany him to the grouse-moor? It is the fag-end of the London season of 1903. You are bored, and it is all Mayfair to a hock-and-seltzer that the fates have got you in their sights and that you are going to start to pay for your fat sins just over the page.

Thus, in the dressing-room, so to speak, you and Carruthers are all ready to start the hurdle race. You are still ready when you get into the small boat in a God-forsaken corner of the East German coast, and you are even more hungry for the starter’s gun when you set sail to meet the villains. Then, to my mind, for the next 95,000 words there is anticlimax.’[8]

Outside of The Riddle of the Sands, there are few examples of heroic characters named Carruthers. There is a Bob Carruthers, a con-man who turns good, in Arthur Conan Doyle’s story The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist, which was published seven months after The Riddle of the Sands. And the narrator of Somerset Maugham’s 1930 short story ‘The Human Element’ unexpectedly meets a Humphrey Carruthers in a hotel in Rome. Wearing a dinner jacket and a boiled shirt, he is balding with undistinguished features. The narrator belatedly remembers that he had known him a little at Oxford, and that he had disliked him: ‘I have never looked on him as quite human.’ But as in many of Maugham’s stories, this unlikely figure has a surprising and poignant story of heartbreak in a hot climate to share. Fleming was a great admirer of Maugham, author of the classic early piece of spy fiction Ashenden, and mimicked this type of story brilliantly in ‘Quantum of Solace’ [9]. However, this Carruthers isn’t a dashing secret agent type but, as in The Riddle of the Sands, an official in the Foreign Office.

If there was a seed for Fleming repeatedly using the name in this way, I think it was a short story by his older brother Peter. Titled ‘Ace High’, he wrote this for BBC radio’s National Programme, and it was first broadcast on 20 April 1934, after which it was published in the BBC’s weekly magazine The Listener [10]. Here’s how it opens:

‘This story begins in Guatemala. To be exact, it begins on the aerodrome outside the capital of Guatemala, and it begins very early in the morning, because in those days – it was about five years ago – the air mail for Mexico used to take off as soon as it got light.

The air mail, which is run by an American company, carries passengers. On this particular morning there were eleven of us. We stood meekly in the Customs shed, next door to the hangar, watching our suitcases being weighted by two small, suspicious men in straw hats. There was a heavy Christmas mail going north, and no one was allowed to take more than the minimum weight of luggage.

There was one other Englishman among the passengers, and naturally I noticed him at once. As a matter of fact, he was a very noticeable person. He was tall, and bronzed, and handsome. He had blue eyes and broad shoulders, and he was smoking a pipe. One cheek was furrowed by an intriguing scar. His suitcase was plastered with a galaxy of labels, all very exotic. He was a striking figure.

But striking in a very conventional way. That was the curious thing about him. It may sound far-fetched, but he conformed so aggressively to type that he seemed really rather an oddity. The trouble was that he was so exactly like the hero of almost any story in a magazine; he was too good to be true. And on top of it all – on top of his blue eyes, and his hatchet face, and his clean limbs – it turned out that his name was Carruthers. That made it harder than ever to believe he was a real person, because the heroes in the magazine stories that I’d read had practically all been called Carruthers.’ [11]

It’s notable that this is by Ian’s brother, of course, but also that it’s about the concept of fictional heroes, and a particular type of fictional hero at that; it seems too much of a coincidence that Ian landed on the same surname when describing how he came to christen his own tall, bronzed, handsome facially scarred protagonist. Ian and Peter were both thriller fans from boyhood, and one can easily imagine that this is an observation that had come up between them: ‘Why are the heroes always called Carruthers?’ And even if they hadn’t discussed it between themselves, it is highly probable that Ian would have either heard or read this story. Peter was not just his brother but a famous writer, guiding the way to the profession Ian would eventually join. After its broadcast and subsequent publication in The Listener, ‘Ace High’ was included in Nine O’Clock Stories, a collection featuring pieces written for the same BBC programme by a diverse group of authors, including Dorothy L Sayers and Graham Greene (the latter being one of Ian’s favourite writers). It was also reprinted in several magazines, and in 1942 was collected in Peter Fleming’s A Story To Tell, which he dedicated to their brother Michael, who had died from war wounds in France two years earlier.

‘Ace High’ also has an element of self-deprecation and self-awareness. Scar aside, Peter himself fitted the physical description of Carruthers in the story, and just as the story’s narrator is distrustful of the man because he looks too good to be true, people sometimes wrote Peter off due to his looks. But unlike the Carruthers in the story, who boasts enigmatically of having been living with Mayan Indians to play up an image, Peter was a genuine explorer, and before long would prove himself to be a genuine hero. During the Second World War, he became a Captain in the Grenadier Guards; was injured and reported killed in action in Norway and was mentioned in dispatches; led a small commando force codenamed the ‘Yak Mission’ under the auspices of the Special Operations Executive in northern Greece; and worked on numerous intelligence and deception operations in Asia. In the latter role, he became friends with one of his colleagues, the best-selling thriller-writer Dennis Wheatley, who described him in his memoir The Deception Planners:

‘Unlike many authors of travel books, who turn out to be pale, bespectacled little men, [Peter’s] bronzed, tight-skinned face always gave the impression that he had just returned from an arduous journey across the Mongolian desert or up some little-known tributary of the Amazon. His lithe, sinewy figure, dark eyes and black hair reminded one of a jaguar, until his quiet smile rendered the simile inappropriate. Physically, he was as fit as any troop-leader of Commandos and, in fact, he had been Chief Instructor at the London District Unarmed Combat School before being sent out to initiate deception in the Far East. He was always immaculate in the gold-peaked cap and freshly-pressed tunic of his regiment, the Grenadier Guards. There was only one thing I disliked about Peter. He smoked the foulest pipe I ever came within a yard of, and when he used to sit on the edge of my desk puffing at it, I heartily wished him back in the jungle. But we were most fortunate in having such a courageous, intelligent and imaginative man as our colleague for the war against Japan.’[12]

In ‘Ace High’, the narrator feels guilty for distrusting Carruthers because he looks too much like ‘the strong silent heroes of fiction’: ‘Everybody, after all, is acting a part most of the time’. Peter’s short story ‘A Story to Tell’, first published in 1937, features a character with some similarities to this:

‘Hopkinson was tall and athletic and handsome in a rather histrionic kind of way, and he had a charming smile; he was intensely unpopular.’[13]

Hopkinson loves the sound of his own voice, and is also something of a fantasist:

‘Many men – most men – dramatize themselves at times. Hopkinson did so incessantly, but in a peculiar and specialized way. The things that happened to him he saw, not in relation to the present and himself, but in relation to the future and an audience. He valued experience almost entirely for its potentialities as narrative.’

These two stories weren’t the only forays Peter Fleming made into sending up the conventions of the thriller’s heroes. In August 1934, four months after the broadcast of ‘Ace High’ on the BBC, Jonathan Cape published One’s Company, his book-length account of his journey to China the previous year. In Chapter Two, he described going through customs in Russia:

‘My brother Ian, recently returned from Moscow where he had been acting as Reuter’s Special Correspondent during the trial of the Metro-Vickers engineers, had given me, by way of a talisman, a photostat copy of a letter he had received from Stalin. Stalin corresponds seldom with foreigners, and the sight of his signature, negligently disposed on top of a suitcase otherwise undistinguished in its contents, aroused in the officials a child-like wonder. Their awe was turned to glee when they found an album containing photographs of an aboriginal tribe in Central Brazil. Had I really taken them? Indeed? They were really very good, most interesting. … Even the Bolsheviks, it seemed, were travel-snobs.

I parted with the officials on the most friendly terms, but with a slightly uneasy conscience, for I had 200 roubles in my pocket. They came, like Stalin’s letter, from my brother Ian, and they were contraband.’

By Chapter V, he had boarded the Trans-Siberian Express:

‘Everyone is a romantic, though in some the romanticism is of a perverted and paradoxical kind. And for a romantic it is, after all, something to stand in the sunlight beside the Trans-Siberian Express with the casually proprietorial air of the passenger, and to reflect that that long raking chain of steel and wood and glass is to go swinging and clattering out of the West into the East, carrying you with it. The metals curve glinting into the distance, a slender bridge between two different worlds. In eight days you will be in Manchuria. Eight days of solid travel: none of those spectacular but unrevealing leaps and bounds which the aeroplane, that agent of superficiality, to-day makes possible. The arrogance of the hard-bitten descends on you. You recall your friends in England, whom only the prospect of shooting grouse can reconcile to eight hours in the train without complaint. Eight hours indeed … You smile contemptuously.

Besides, the dignity, or at least the glamour of trains has lately been enhanced. Shanghai Express, Rome Express, Stamboul Train – these and others have successfully exploited its potentialities as a setting for adventure and romance. In fiction, drama, and the films there has been a firmer tone in Wagons Lits than ever since the early days of Oppenheim. Complacently you weigh your chances of a foreign countess, the secret emissary of a Certain Power, her corsage stuffed with documents of the first political importance. Will anyone mistake you for No. 37, whose real name no one knows, and who is practically always in a train, being ‘whirled’ somewhere? You have an intoxicating vision of drugged liqueurs, rifled dispatch-cases, lights suddenly extinguished, and door-handles turning slowly under the bright eye of an automatic…’

There’s a lot in here that sounds like work Ian would produce in decades to come: ‘That long raking chain of steel and wood and glass…’, ‘The metals curve glinting into the distance, a slender bridge between two different worlds…’; the reference to E Phillips Oppenheim and the amusing synopsis of several familiar elements from spy stories. But what is most fascinating here is that Peter Fleming deliberately portrays himself as not the sort of person who would have an exciting adventure, even though by most people’s standards his journey is highly adventurous. He is pointing out that in reality train journeys like this are long and uncomfortable, not glamorous and melodramatic as they are in fiction. And like Carruthers and Hopkinson, he is a fantasist, albeit a wryly self-aware one. As in ‘Ace High’ and ‘A Story to Tell’, he is asking if we aren’t all fantasists from time to time, reading our lives as thrillers.

I’ll look at this concept in more detail in the next part of this essay. It ripples through the subsequent decades of thriller-writing, and I think some of the details overturn a few common conceptions about the genre and several of its landmarks, including Ian Fleming’s work, as well as stretching beyond the thriller.