Uncut Gem

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

A man runs across a beach, desperate to reach a plane at the far end of it. He hands something to the pilot just as it takes off. The plane rises into a bank of fog, whereupon it erupts into a ball of flame. The man rushes toward the crash, scrambling through the wreckage until his foot hits something. Looking down, he sees a small metal canister. He picks it up and fumbles it open. Diamonds spill into his hand…

If this sounds like the pre-titles sequence of a Bond film, it’s not a coincidence. It is a pre-titles sequence, and it’s from a screenplay based on one of Ian Fleming’s books. For the past 45 years, its existence has remained unknown outside the small group of men who tried to film it.

I first became aware of the story when reading The Letters of Kingsley Amis. I was intrigued by a short letter he had sent fellow writer Theo Richmond in December 1965:

‘I have been having a rather horrible time writing a story outline for one George Willoughby. Based on an original Fleming idea. Willoughby and the script-writer change everything as I come up with it. I gave W. the completed outline five days ago and he has been too shocked and horrified and despairing to say a word since. However, he has already paid me. (Not much.)’¹

I smiled at the familiar writer’s complaint, then stopped in my tracks. What ‘original Fleming idea’? I’d never heard of it, and couldn’t find any reference to it anywhere else. I decided to investigate. My first step was to contact Zachary Leader, Amis’ biographer and the editor of his letters, to ask him if he had any idea where the outline might be. He wasn’t sure, but put me in touch with the Huntington Library in California and the Harry Ransom Center in Texas, both of which hold Amis’ papers. Researchers there sent me inventories of everything they held, and I started trying their patience by asking them to go through boxes that sounded as though they might conceivably contain the outline. After weeks of this, and feeling as though we had examined practically every scrap of paper Amis had saved, I called time. Wherever Amis’ outline was, it didn’t appear to be stored with the rest of his papers.

My attention turned to the other clue mentioned in Amis’ letter: ‘one George Willoughby’. And here I got a little luckier. Willoughby, I discovered, was a Norwegian who had moved to London and become a medium-sized fish in the British film industry. In 1951, he had been an associate producer on Valley Of Eagles, directed and co-written by Terence Young and filmed at Pinewood, the studio owned by The Rank Organisation, at that time Britain’s largest film company. Young went on to direct several of the Bond films, shooting large parts of them at Pinewood.

In 1954, Willoughby had been an associate producer on Hell Below Zero, an adaptation of a Hammond Innes novel made by Warwick Films. Warwick was a company founded by Irving Allen and Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli, and it specialised in making relatively inexpensive but exciting action films. In 1962, Cubby Broccoli would part ways with Allen and form a new company, Eon, with Harry Saltzman. One of the scriptwriters for Hell Below Zero was Richard Maibaum, who Broccoli would take with him: he would go on to have a hand in the scripts to over a dozen Bond films.

Finally, in 1957 George Willoughby had been the associate producer on Action Of The Tiger, another Terence Young-directed film, this one featuring a young Sean Connery. So he had worked with three of the men who would become key players in the Bond franchise: Broccoli, Young and Maibaum. But while this was intriguing, I was no closer to finding the outline of the ‘original Fleming idea’ Amis had written for Willoughby.

But after several months of consulting authors’ societies, literary agents and film libraries, I finally found what I was looking for. To my surprise, a lot of the story had been hiding in plain sight since 1989 in a book called In Camera, a volume of memoirs by Richard Todd.

~

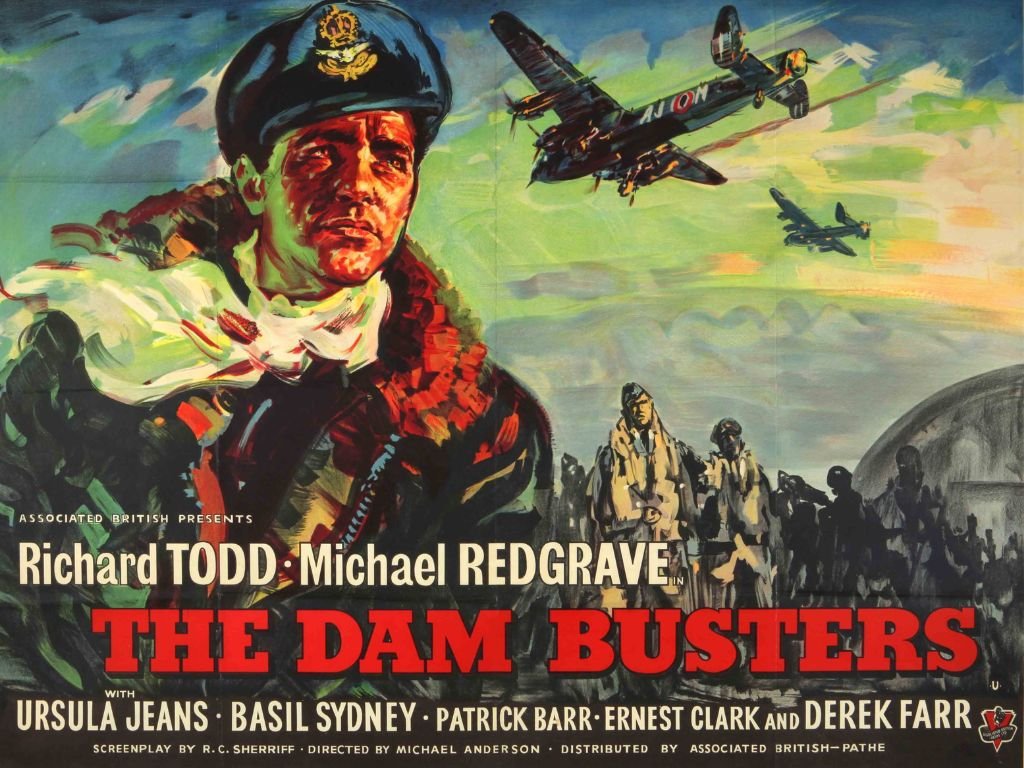

A poster for The Dam Busters (1955)

During the Second World War, Todd had served in the Army’s 6th Airborne Division—he was the first man of the main force to parachute out over Normandy on D-Day. After the war, he had become one of Britain’s biggest film stars. He was nominated for an Oscar for The Hasty Heart in 1949, after which he went on to play several leading roles, including starring opposite Marlene Dietrich in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright. However, he is probably best remembered today for playing Wing Commander Guy Gibson in the classic war film The Dam Busters.

Like Willoughby, Todd had also worked with many of the people who were to become central to the James Bond series. Although he was a contract player with Rank’s main rivals, the Associated British Picture Corporation (ABPC), who were based at Elstree Studios, he sometimes worked on ‘loan-out’ for Rank, for example on Venetian Bird, an adaptation of a Victor Canning thriller.

He had also made a film for Cubby Broccoli: The Hellions, a quasi-Western shot in South Africa in 1961. The following year, he was one of the star-studded cast of The Longest Day, an adaptation of Cornelius Ryan’s account of D-Day. Todd played Major John Howard, who had been his superior officer on the day in real life. On the set in Caen in France, he met a ‘rather shy’ young Scottish actor with a small part in the film: Sean Connery.²

Richard Todd with Eva Bartok in the 1952 film Venetian Bird, also known as The Assassin, an adaptation of a Victor Canning thriller

In April 1962, while Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman were busy finalising their contract with United Artists for the first Bond film, Dr No³, Todd was informed that his contract with ABPC would not be renewed the following year. This was a body blow: it meant that he would now have to fend for himself in the jungle of Britain’s rapidly declining film industry, which was under increasing pressure from Hollywood. But he had at least one iron in the fire, in the form of his friend George Willoughby, who ‘had secured an option on the screen rights of an Ian Fleming book, The Diamond Story [sic], an intriguing exposé of illicit diamond-buying in Africa and of the undercover activities of agents who worked to counteract it’.⁴

So here it was: this was the elusive project Amis had been working on. The Diamond Smugglers was Fleming’s first foray into full-length non-fiction, and apart from the guidebook Thrilling Cities remains the only one of his books not to have been filmed. It was originally published in 1957, collecting a series of articles in The Sunday Times in which Fleming had explored the shady world of diamond trafficking. A new edition of the book was published in 2009, with an introduction by Fergus Fleming, the writer’s nephew. ‘The success of Bond tends to eclipse Ian Fleming’s other talents,’ he tells me. ‘It’s often forgotten that he was also an accomplished journalist, travel writer and children’s author.’⁵

Ian Fleming had become fascinated by the illegal trade in gemstones in 1954, when he had discovered that the world’s biggest diamond-seller, De Beers, had set up its own private intelligence agency, the International Diamond Security Organisation, to try to combat it. IDSO was run by Sir Percy Sillitoe, who had previously been the head of MI5. Fleming met with Sillitoe and other diamond industry insiders, and used much of what he learned as background material for Diamonds Are Forever, largely set in the United States.⁶ The title of the novel was drawn from De Beers’ slogan.

Three years later, Fleming was drawn back into the world of diamonds. IDSO had blocked several plots by international criminal networks to bring diamonds illegally out of the mines of South Africa, Sierra Leone and elsewhere, and had been disbanded. Sillitoe, irritated that he and the organization had not been given more credit for their successes, decided to publish a book about it. His intention was for it to be a sequel to his 1955 memoir Cloak Without Dagger, and with that in mind he commissioned one of IDSO’s senior agents, John Collard, to ghost-write an account.

Collard was an old hand in the espionage game. He had been in MI5 in the early part of the Second World War, but had then moved to the counter-intelligence agency MI11, becoming its head by 1946. He then rejoined MI5 and played a major role in the capture and conviction of the ‘atomic spy’ Klaus Fuchs, before heading off to South Africa to join IDSO.⁷

Collard revisited his and other agents’ reports and wrote the book. Sillitoe sent the manuscript to Denis Hamilton at The Sunday Times for his view; Hamilton liked it, but Leonard Russell on the paper felt that a professional journalist would be able to spice it up. They suggested that Ian Fleming, who worked for the paper, interview Collard with the aim of producing a series of articles. All involved agreed, and so in early April 1957 Fleming took an Air France Caravelle to Tangiers to meet John Collard. The two men quickly established a rapport, and Fleming started work.⁸

This mainly consisted of editing and redrafting the original manuscript. Collard had detailed the organisation’s frustrations, failures and successes in clear, lively prose, and it probably would have sold well had it been published as it was. But it was no thriller. Fleming went through the text, cutting anything he felt was dull or overly complicated and heightening the most exciting passages as only he knew how. He also adapted information from Collard’s source material: one IDSO agent’s report in Collard’s papers has ‘Passage omitted I.F.’ and ‘Name omitted I.F.’ all over it in Fleming’s distinctive scrawl.⁹

The biggest change Fleming made was not to the content, but to the perspective. Collard had written the book as though Sillitoe were the narrator. Fleming kept most of Collard’s material, but rewrote it so that he, Ian Fleming, became the narrator, the intrepid investigative journalist flying out to Tangiers to interview the mysterious hero of the tale, who he made Collard instead of Sillitoe.

This switch was clever in several ways. Firstly, Sillitoe was at that point nearly 70 years old, and was not nearly as compelling a subject as Collard, who was in his mid-forties and therefore a man with whom readers could more readily identify. Sillitoe was largely a desk man, while Collard had seen extensive action in the field, both with MI5 and with IDSO—indeed, he wrote of his own actions in the third person throughout his manuscript. Sillitoe was the M figure of the organisation, and Fleming must have realized that the public would be drawn to someone more like Bond.

This shift of focus from Sillitoe to Collard allowed Fleming to create something more reminiscent of his own famous thrillers, as well as to add some local colour and texture. The framing device of the interview allowed Fleming to break up Collard’s long passages of close exposition about the diamond industry with some of his own brand of intrigue, bringing in references to life in Tangier, other spies such as Richard Sorge and Christine Granville and, of course, James Bond.

Either prompted by others or on his own initiative, Fleming also gave several of the people featured in the book different names, including Collard. The book discussed at length how IDSO had foiled several unscrupulous gangs, so there might have been some concern about blowback following publication. For Collard, Fleming chose the rather Bond-ish ‘John Blaize’—in the germ of a scene in one of his notebooks, he had had Miss Moneypenny suggest ‘Major Patrick Blaize’ as a cover name for Bond.¹⁰

Fleming portrayed Collard/Blaize as a quieter, shyer character than Bond, although readers would learn that he owned 24 fine white silk shirts and intended to spend 48 hours gambling intensively in Monte Carlo ‘to wash the last three years and the African continent out of his system’.¹¹

In 1965, Leonard Russell wrote to Collard to ask him about his recollections of Fleming for a biography he was writing of him with John Pearson—Pearson eventually took over the job completely—and Collard gave a detailed account of how the book had come about and how he had met Fleming. In much the same way he’d ghost-written himself into Sillitoe’s memoir, he also wrote this up in the third person. He reveals the week included them playing golf together and attending parties, and that they kept in touch in subsequent years:

‘In the bar at the Royal St Georges or Rye Golf Club, they could sometimes be seen having a private yarn.’¹²

The two men evidently got on well in Tangiers, but Fleming’s presentation of their meetings in the book is largely fiction. No doubt he asked Collard for clarification on some points, but his work was largely editorial: he took passages from Collard’s book, rearranged and simplified them, and then had ‘Blaize’ speak them aloud while he, Fleming, supposedly leaned in and listened, interjecting occasional questions. In this way, the book took on the tone of a fascinating secret story being told in a darkened corner of a bar in the tropics, automatically giving it more vigour. Fleming could probably have done most of this work in London—but then, that wouldn’t have been as exciting, or got him a few days’ golf and partying in Tangiers.

~

To pre-empt any legal difficulties, Fleming sent proofs of his version of the book to The Diamond Corporation, De Beers’ distribution arm in London. The move didn’t work. Although the company initially appeared pleased with the text, it later took exception to several elements, and Fleming was forced into rewrites.¹³ But finally, in September 1957, the articles began to be serialised in The Sunday Times. Readers learned about ‘Monsieur Diamant’, a ‘big, hard chunk of a man with about ten million pounds in the bank’. Outwardly a respectable entrepreneur, his diamond-fencing activities had made him ‘the biggest crook in Europe, if not in the world’. Another episode concerned a bravado attempt to fly 1,400 stolen diamonds out of Chamaais Beach in South-West Africa, which failed when the plane crashed on take-off.

The articles were collected to form a book, titled The Diamond Smugglers, which was published in November with an introduction by Collard (under the Blaize pseudonym). The book didn’t differ a great deal from the manuscript Collard had originally written, but it had been souped up, texture had been added and, above all, Fleming’s name had been appended to it. As a result, it received a level of marketing almost equal to that afforded to the Bond novels at the time.¹⁴

Fleming was happy with his scoop, but not entirely satisfied with the way the project had turned out. On the fly-leaf of his own copy of the book, now stored at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, he noted:

‘This was written in 2 weeks in Tangiers, April 1957. The name of the IDSO spy is John Collard. Sir Percy Sillitoe sold the story to the Sunday Times & I had to write it from Collard’s M.S. It was a good story until all the possible libel was cut out. There was nearly an injunction against me & the Sunday Times by De Beers to prevent publication of the S. T. serial. Rightly, they didn’t like their secrets being sold by an employee. Lord Kemsley & Collard shared the profits of this—a third each, which was a pity as I sold the film rights to Rank for £12,500. It is adequate journalism but a poor book & necessarily rather “contrived” though the facts are true.’¹⁵

Perhaps as a result of his irritation at the suppression of some of the story’s more exciting aspects, Fleming’s view was overly pessimistic. The fact that Rank was prepared to pay a sizeable amount for the rights to a compilation of newspaper articles he had written in a fortnight was a sign of the growing interest in his work from the film industry. In 1954, Gregory Ratoff had taken a six-month option on his first novel, Casino Royale, for $600, and shortly after that CBS had bought the television rights to the same book for $1,000. The following year, Rank had snapped up the rights to Moonraker for £5,000. Casino Royale was rapidly made into an hour-long TV adaptation, with Barry Nelson as James ‘Jimmy’ Bond and Peter Lorre as Le Chiffre. Rank’s Moonraker film never got off the ground.¹⁶

Rank was, initially at least, keen to publicise the fact that it had bought the rights to the book. The Bookseller noted that it had bought the rights for ‘an unusually high figure’, and had ‘commissioned Ian Fleming to prepare the film treatment’¹⁷, and ‘The Diamond Smugglers Story’ was included in Rank’s programme for 1958 along with The Thirty-Nine Steps and Lawrence of Arabia (both of those were prematurely announced, being released in 1959 and 1962 respectively). But 1958 passed, and the film didn’t materialize.

~

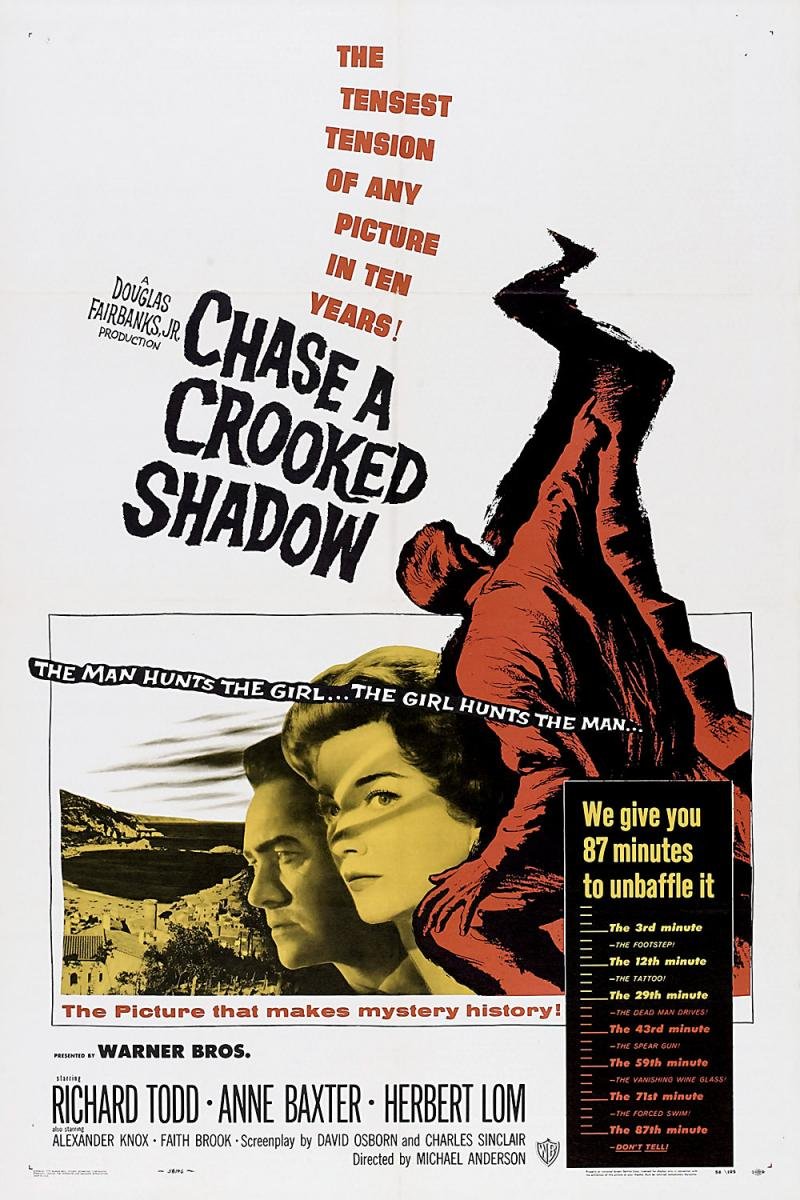

Poster for Chase a Crooked Shadow (1958)

That’s the traditional story of The Diamond Smugglers, mentioned in passing in dozens of books and articles. A slightly obscure Fleming work, not featuring James Bond. A success, but not one of his greater ones. The film rights sold, but no film made. Case closed.

Well, not quite. There were attempts to film The Diamond Smugglers, serious and prolonged attempts, as Todd’s memoir showed. I contacted the actor’s agent, but was told that due to frailty and a hazy memory he didn’t feel he could add to what he had already written. This was understandable: Todd was approaching ninety and, unknown to me, suffering from cancer. I had by now also contacted John Collard’s family, who kindly provided me with a great deal of material, including both his relevant correspondence from the time and the original manuscript of his book. Adding this to the information in Todd’s memoirs and other sources, I started to piece together the rest of the story.

Willoughby set up his own production company in 1959, and at some point between then and 1962 obtained the film rights to The Diamond Smugglers. In a letter to a former colleague in 1965, John Collard wrote that he had met Willoughby ‘about five years ago at the request of Ian Fleming’.¹⁸

From subsequent events, it seems that Rank may have told Willoughby that they had given up on trying to adapt the book, but that if he could put together the elements of a commercially viable film, they would distribute it. They later did just that with another Willoughby production, Age of Innocence, which had featured Lois Maxwell and Honor Blackman.

Todd and Willoughby became partners in 1962, and set to work: Derry Quinn, who had worked as a story supervisor on Chase A Crooked Shadow, a thriller Todd had made in 1958, was hired to write a treatment. As well as Todd’s contacts within the industry and star power—presumably the original intention was for him to play Blaize—the actor also knew South Africa. While making The Hellions, he had been struck by the potential for a film industry there: it had widely varying scenery and climate, a lot of investors looking for overseas outlets, and a large pool of English-speaking actors.¹⁹

As The Diamond Smugglers took place in that part of the world, Todd now returned to his South African contacts, inviting to London Ernesto Bisogno, a businessman he had met on his Hellions trip who had dabbled in small-scale film production and was now forming a production company in Johannesburg. Bisogno was accompanied by an official of the South African Industrial Development Corporation, who Todd had also met the previous year. Their reactions to the project were apparently very favourable, and Todd was optimistic that he would be able to persuade ABPC to distribute the film once it was made. However, work on the screenplay was slow, with Todd’s flat becoming ‘a charnel-house of abandoned drafts and screen treatments’.²⁰ Fleming’s book was essentially a series of unconnected episodes: crafting an exciting, coherent and commercial script from them would prove no easy task.

In April 1963, a full year after starting work on the project, the two men had a breakthrough: John Davis, the head of Rank, put them in touch with Earl St John, who was in charge of productions at Pinewood. St John had been an executive producer on Passionate Summer, a film Willoughby had produced in 1958. He liked their pitch, and as a result Rank funded a trip to South Africa and South-West Africa (now Namibia) in May 1964 to scout locations in which to set the screenplay for The Diamond Smugglers.²¹

~

Season of Doubt, a 1968 spy thriller by Jon Cleary set in Beirut

By now a new writer had arrived on the scene: the Australian Jon Cleary, then best known for his novel The Sundowners, the film of which had starred Robert Mitchum and Deborah Kerr and had been nominated for five Academy Awards. Now in his nineties, he still vividly recalls his work on The Diamond Smugglers. ‘My doctor says my body is ninety but my head’s fifty,’ he laughs when I speak to him on the phone from his home in Sydney. According to Cleary, Rank had originally bought the rights to the book because of Fleming’s name. ‘They disowned it when they realised it was a grab-bag of pieces he had written one wet weekend. There was no story. So they put it on the shelf.’²²

But now The Diamond Smugglers had another shot. It was not only back on Rank’s radar—they were putting up money to develop it. Accompanying Todd, Willoughby and Cleary on the trip to Africa was the American director Bob Parrish, who, according to Cleary, had agreed to direct the film subject to a satisfactory script being developed. Cleary and Parrish both lived in London and knew each other; Cleary says Parrish put him forward for the project. Parrish, who had won an Oscar as an editor, had directed an adaptation of Geoffrey Household’s A Rough Shoot, from a script by Eric Ambler, and Fire Down Below, co-produced by Cubby Broccoli.

‘We landed in Johannesburg on a Sunday afternoon,’ Cleary remembered. ‘There were three thousand people there to meet us at the airport! We stayed in the Langham Hotel, which was the place to be. Everything was laid on for us, and all kinds of avenues of research were opened—I knew nothing about diamonds. One day, a European woman—Contessa something-or-other—turned up at my hotel room to discuss the business, and emptied her chamois bag, spilling diamonds onto the table. It was about three or four million Rand, just sitting there!’

After spending a few days in South Africa, where they scouted locations in Johannesburg, M’Tuba’Tuba and Pretoria, the group flew to South-West Africa’s capital, Windhoek. They were shown around by Jack Levinson and his wife Olga, who lived in a castle-like residence that had been built for the Commander-in-Chief when the country had been a German colony. The Levinsons were ideal guides for their mission: as well as being the city’s mayor, Jack was also a lithium entrepreneur who had discovered diamonds on the Skeleton Coast, while Olga had recently published a history of the country.²³

By now, the Bond films were big business, and with the release of Goldfinger in September, about to become a global phenomenon. Was the intention to leverage Fleming’s material into a Bond-style plot? Not according to Cleary: ‘It was always going to be much more realistic than the Bond films. We wanted to make use of the fact that we had these remote, exotic locations, but craft something much more down-to-earth, that nobody had seen before.’

Cleary, like Derry Quinn before him, was desperately looking for a way to connect the disparate elements of Fleming’s book into an exciting plot. In South-West Africa, he finally hit upon an idea. ‘Bob liked it. We told Richard—it would involve him being the villain, for a change. He jumped at it. The idea was for Steve McQueen to play the lead. I’ve forgotten who they wanted for the girl, but it was one of the top stars.’

McQueen, who had become well known after The Magnificent Seven in 1960, had just made The Great Escape, which had catapulted him to greater fame. Whether or not he would have been interested or available for The Diamond Smugglers is another question, but it’s fascinating to think of him in a Fleming adaptation.

Cleary’s original idea for the script was based on a story he had heard while the team were scouting the Skeleton Coast, about a man who sets up a model aeroplane club in the De Beers’-protected town Oranjemund, and then uses the model planes to try to smuggle some diamonds out. Fired up with the potential of this idea, Cleary ‘went away and wrote a screenplay’. I ask him to repeat this to be certain I’ve heard correctly. There are no references to a completed screenplay in Todd’s memoirs—or anywhere else. A script of an unfilmed Ian Fleming book, written in the Sixties by a well-known novelist, with funding by Rank… well, that would be something. ‘Did you keep a copy?’ I ask quietly. Cleary chuckles. ‘I’m afraid I’ve never been a hoarder,’ he says, and my heart sinks. He tells me that the State Library of New South Wales has his papers, but that they often call, begging him to send them his latest manuscript ‘before I throw it out’.

This doesn’t sound hopeful, but I contact the library anyway. And they have it. After obtaining permission from Cleary and his literary agency, I am sent a copy. I crack it open, and stare at the title page with amazement. ‘The Diamond Smugglers by Ian Fleming. Draft screenplay by John Cleary.’ I had gone looking for Amis’ story outline, and had instead found a completed screenplay.

~

The script is dated October 28 1964, and is 149 pages long. It begins:

‘EXT. BEACH. SOUTH WEST AFRICA. EARLY MORNING.

We open on a LONG SHOT of a desert, grey-blue and cold looking in the dawn light…’²⁴

The protagonist has been renamed: instead of John Blaize, he is now Roy O’Brien, a tall, quiet American secret agent who is sent to a diamond mine in Johannesburg under cover as a pilot. His mission: to infiltrate and break up a ring of smugglers preparing to make a huge deal with the Red Chinese. O’Brien reads very much as though written with McQueen in mind. We are told he is ‘marked with the sun and the scars of a man who has spent a good deal of his life in the outdoors’ and that ‘he was a boy once quick to smiles’ but is now ‘a man who has seen too much of sights that did not provoke laughter’. He is quick-witted, laconic, but very likeable.

We first meet him in Amsterdam, where he is staking out Vicki Linden, a beautiful young South-West-African diamond-smuggler of German descent. She is reminiscent of the character Tiffany Case in Fleming’s novel Diamonds Are Forever, but somewhat softer and more naive (without being irritating). He follows Vicki to South Africa, and she tells him her ambition is to have a diamond ‘for every day in the week’. He asks how far she has got in this and she wrinkles her nose and replies ‘Only Monday’, to which he retorts: ‘Give me the chance and I’ll try and dig up Tuesday for you.’

Despite the change from Blaize to O’Brien and the addition of new characters, Cleary’s screenplay is remarkably faithful to the tone of Fleming’s book, and takes a lot of cues from it. Cleary used locations, incidents, technical information and a lot of other elements and ideas from the book, and wove a thriller plot around them. The opening sequence is clearly inspired by the failed attempt to fly diamonds out from Chamaais Beach, although this time the plane doesn’t simply crash but explodes mid-air. China’s increasing interest in the illegal diamond trade, discussed at several points in the book, becomes the political backdrop of the plot; the description of security measures employed by mining companies is dramatised in a scene in which O’Brien is X-rayed; like Collard/Blaize, he makes use of a safe house in Johannesburg’s back streets; and so on.

It is a very different beast to the Bond films. There are no nuclear warheads or hidden lairs: it is, as Cleary says was the intention, a gritty, down-to-earth thriller. Nevertheless, there are some suitably baroque and Fleming-esque touches. One of the villains is a diamond-smuggler called Cuza, who weighs over four hundred pounds ‘but walks with a delicate step’ and likes eating chocolates: ‘Stone-bald, he wears dark glasses; a balloon head rests on a balloon body; he could be a clown or a killer.’

Cuza and his black sidekick Daniel work out of a windswept drive-in cinema projectionist’s office. In one memorable scene, Daniel stalks O’Brien with a sniper rifle from his position on a catwalk running along the top of the cinema screen.

Cuza is in competition with a villain in a similar mould to Fleming’s: Steven Halas is a wealthy German South-West-African businessman who likes giving lavish parties (at which he serves Bollinger ’55) and taking photographs of big game, but beneath the veneer of sophistication he is greed personified. However, the real villain of the piece is revealed in the final act to be Ian Cameron, a womanising Scot who is the mine’s field manager, and who is gently reminiscent of both Bond and Fleming. This, presumably, is the role that had been earmarked for Todd.

As well as drawing incidents and ideas from Fleming’s book, the script is faithful to its tone, especially in its evocation of the sticky climate of fear and temptation permeating a diamond mining community. The shabbiness of O’Brien’s accommodation provokes the script’s one direct reference to Fleming’s best-known creation, when his colleague Spaak is amused at its unsuitability and asks what has become of spies who only operate in five-star hotels. ‘You need a nice low number,’ O’Brien replies, ‘Like 007. Whoever heard of a spy called 42663-stroke-12568?’ ‘What’s that?’ asks Spaak. ‘My social security number,’ comes the dry reply.

Highlights include two brutal hand-to-hand fights, one of which ends with the death of the monstrous Cuza, and a climactic car chase, which happens during an elephant stampede.

All told, the script is a cracker: a taut thriller with believable characters, snappy dialogue and a compelling plot. Its strongest features are its evocation of the Skeleton Coast—you can almost feel the dust and the dirt of this place that ‘breeds seals, jackals and madmen’, as one character describes it—and the subtle shading of the relationship between O’Brien and Vicki. Cleary also added some extra spice to the traditional police/spy story with elements of the Western and film noir, in a manner occasionally reminiscent of Orson Welles’ A Touch Of Evil. His script is free of the troublesome plot holes, inconsistent characterisation and mixed tones common in many films of the time.

According to Todd’s memoirs, in the summer of 1965 Rank signed an option to buy and produce the film, while on 14 June of that year, Willoughby wrote to John Collard to tell him that the production looked like it was back on the table:

‘You may recollect that we met a few years ago in connection with the proposed production of a film based on Ian Fleming’s “The Diamond Smugglers”. Due to various circumstances at the time, these plans did not materialise. It is now a possibility that I shall be able to set up a production on this subject.’²⁵

The letter is headed ‘Willoughby Film Productions Limited’ with an address in Sackville Street in London—but next to it Willoughby typed another address for Collard to reply to: Pinewood Studios, Iver Heath, Bucks.

Willoughby was contacting Collard again because he wanted his permission to use the character of John Blaize (the name O’Brien seemingly having been dropped). As a sweetener, he offered Collard a role as a technical adviser to the production.

Collard replied that De Beers should be consulted about the latest plans for the film, and asked for more details about it: would it be a documentary sticking closely to the book, or partly fictional?²⁶ On 21 June, Willoughby wrote to Collard again, writing that the film he had in mind was a ‘feature entertainment’, which would necessitate departing from Fleming’s book, as that had mainly consisted of ‘a number of incidents without a dramatic story line or link’. He understood that Collard might feel they were straying too far from the facts, but gave a surprising precedent for it:

‘Fleming himself wrote for the Rank Organisation, a film treatment on this subject and although he used the name of John Blaize for the hero, his treatment had, nevertheless, very little to do with the actual articles he wrote for the “Sunday Times”.’²⁷

This is the first mention of the existence of a film treatment for The Diamond Smugglers by Ian Fleming since The Bookseller’s report of its commissioning in 1957—but it would not be the last. On 1 September 1965, Collard received a letter from B.J. Rudd, an old acquaintance, who had enclosed a small cutting from The Sun from 25 August, titled ‘Fleming film’:

‘An 18-page outline for a film about illicit diamond-buying written by Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, is to be turned into a £1,200,000 film.’²⁸

Collard and Willoughby, meanwhile, continued to correspond, with the producer revealing two new pieces of information in a letter on 27 August: a script was being completed by yet another writer, Anthony Dawson (‘who lives not far from you in Sussex’) and that the protagonist’s surname had now been changed from Blaize to Blaine, to avoid confusion with Modesty Blaise.²⁹

For anyone familiar with the James Bond films, the reference to Anthony Dawson is almost surreal: could this be the British character actor who had played Professor Dent in Dr No and who had been the presence (although not the voice) of arch-villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld in both From Russia With Love and Thunderball? It would seem so. Terence Young, who directed all three of those Bond entries, cast Dawson in several of his films, including Valley of Eagles and Action of the Tiger, both of which had had as associate producer one George Willoughby. It seems implausible that there were two Anthony Dawsons who worked on Ian Fleming projects in the Sixties, and that Willoughby collaborated with both. Dawson’s son confirms that his father lived in Sussex during this period, and wrote several film scripts.³⁰ Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to locate any material relating to The Diamond Smugglers.

A few weeks later, Barbara Bladen, a critic at the San Mateo Times in California, reported breathlessly on the film in her column:

‘We’ll have to start getting used to someone else playing James Bond in the Ian Fleming stories! Sean Connery has gone back to being Sean Connery and the Fleming pictures roll on. Latest before the cameras is “The Diamond Spy” on location in South Africa, Amsterdam and the Baltic coast of Germany. Richard Todd will play the slick agent. The author first wrote the book as a series of newspaper articles in 1957 and came out in book form as “The Diamond Smugglers.”’³¹

The changing of the protagonist from a newly coined character to the world-famous James Bond is probably either Willoughby or Bladen’s hyperbole—perhaps even a way around the fact that they had not yet resolved what to call the character. The locations listed are intriguing: South Africa and Amsterdam were both featured in Cleary’s 1964 screenplay, but the Baltic coast of Germany was not. Could there have been another script by this time—or did Willoughby merely have an idea for one?

The title The Diamond Spy, which now started appearing in the press, did not please John Collard. On 3 January 1966, he wrote to Willoughby at Pinewood:

‘If the revised title is seriously proposed, I am afraid that as far as I am concerned the film will start off on the wrong foot, whether it is described as fictional or coincidental, and the object of this letter is to advise you in the friendliest possible manner to bear in mind my personal interest and the need to consider the risk of libel.’³²

In a more placatory hand-written postscript, Collard explained that Fleming had originally planned on calling his book The Diamond Spy, but had changed it at Collard’s request: ‘The description “spy” carries with it a derogatory meaning,’ he explained to Willoughby, ‘and quite apart from its inappropriate use to describe “Blaize”, I myself take strong exception to it.’ The word ‘spy’ was often used in books and films at the time, and Fleming had of course used it in one of his titles, but Collard had worked for MI5, and in that and other intelligence agencies, the word was usually used to refer to informants and traitors.

Collard’s letter seems to have been the first between the two men since August 1965, but it begun another flurry of correspondence. Willoughby immediately tried to reassure Collard that The Diamond Spy was merely a working title, which they were using ‘because this is the title Fleming used for his story-line’. He invited him to lunch the next time he was in London to tell him more about the film.³³

By now, Willoughby had hired Kingsley Amis as a ‘special story and script consultant’. This news was reported in the American film industry magazine Boxoffice in January 1966:

‘Kingsley Amis, novelist, critic and authority on the work of Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, has been engaged as special story and script consultant on the new £11/4 film of Fleming’s “The Diamond Spy”, it was announced last week by British producer George Willoughby. The film, to be made early next year by Willoughby, in association with Richard Todd’s independent company, is based on a story outline written by Ian Fleming but never completed by him. This outline was drafted by Fleming following his own investigations into international diamond smuggling, which he wrote up as a series of articles for a Sunday newspaper in 1957. Later, these articles were collected and published in book form under the title of “The Diamond Smugglers”.

Now Amis, author of the recently published “James Bond Dossier”, has been called in as a Fleming expert to develop the story, characters, situations and incidents so as to give “The Diamond Spy” film an authentic Fleming flavor. When he has completed this task, W. H. Canaway, who wrote the script of “The Ipcress File”, will take over all the material, from which he will write the final screenplay.’³⁴

This article repeated some material that had been published in Boxoffice in the same column a few months earlier³⁵, but the screenwriters’ names were new—and brought a significant amount of prestige and experience to the table. The IPCRESS File, which had been produced by Harry Saltzman and featured the talents of several other Bond alumni, had been a great success, and Amis’ status as a Fleming ‘expert’ would receive another push later the same month, when it was announced that he had been commissioned to write the first James Bond novel since Fleming’s death.

On January 27 1966, Willoughby wrote to Collard to finalise the details of a meeting they were both to attend in London on 4 February:

‘Thos [sic] present at the meeting, in addition to myself, will be Mr Kenneth Hargreaves of Anglo Embassy Productions Ltd., and Mr David Deutsch of Anglo Amalgamated Film Distributors.’³⁶

It seems Willoughby had found yet new partners. Anglo Embassy was the English arm of Joseph E Levine’s Embassy Pictures, which had produced Zulu and The Carpetbaggers. Levine would go on to produce The Graduate, The Producers and The Lion In Winter. Anglo Amalgamated’s main claim to fame was the Carry On films, and in 1964 it had distributed The Masque of The Red Death, which Willoughby had associate-produced. But it was becoming increasingly high-brow, backing the first features of both John Boorman (Catch Us If You Can, released in 1965), and Ken Loach (Poor Cow, released in 1968). It had also released the highly controversial Peeping Tom in 1960.

On January 31, John Collard received a letter from Glidrose Productions: the owners of the James Bond literary copyright. It was from Beryl Griffie-Williams, ‘Griffie’, who had been Ian Fleming’s secretary. She enclosed a newspaper cutting about Anglo Amalgamated Distributors. It seems that in advance of his meeting with Willoughby, Hargeaves and Deutsch, Collard has asked Glidrose what they made of Anglo Amalgamated. Griffie-Williams wrote that the feeling was that they were not very ambitious, and that the resulting film might be ‘mediocre’. She also revealed that Rank were unwilling to sell the book’s film rights, which had been sold to them outright, but that despite Willoughby’s option with Rank being due to expire, the company were prepared to ‘play along’ with him. She added: ‘On checking past correspondence, it does seem that Willoughby will make an entirely different film from the book. He does, I think, intend to create a new character which he can follow up in any subsequent film.’³⁷

This was a potentially crucial point. Three years earlier, another independent producer, Kevin McClory, had provided a massive legal headache for Ian Fleming over Thunderball, and had won the right to remake that film (which he later did, as Never Say Never Again). As a result, Glidrose had sound reasons for wondering whether, were The Diamond Smugglers to prove a box office success, Willoughby and Todd might try to produce sequels to it featuring ‘John Blaine’. And if they did, who would own the rights to this character, who was an amalgam of a real agent, John Collard, a fictionalised version of him created by Ian Fleming, and a further re-imagining by Jon Cleary, Kingsley Amis and several other writers?

~

We don’t know what happened at Collard’s meeting with Willoughby, Hargreaves and Deutsch, but at any rate Willoughby pressed on. On 9 February 1966, another article appeared in The San Mateo Times, headlined ‘Newspaper Stories by Ian Fleming In Film’:

‘“The Diamond Spy”, an unpublished story by the late Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, will be brought to the screen by Joseph E. Levine’s Embassy Pictures in conjunction with Anglo Amalgamated Film Distributors, Ltd. of London, headed by Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy.

The five-million dollar co-production will be produced by George Willoughby, from screenplay by W. H. Cannaway [sic] and Kingsley Amis. Director and cast for the adventure-thriller have not yet been set. “The Diamond Spy” also will be based in part on a series of newspaper articles written by Fleming and published in paper-back form under the title, “Diamond Smugglers”. The story of the smashing of a huge international band of diamond racketeers, it will be filmed in color on location in South Africa, Beirut, Amsterdam, Germany and London. Embassy Pictures will distribute the film worldwide, with the exception of the United Kingdom. The last film venture involving the two companies was “Darling”, which has won acclaim at both the box-office and from critics everywhere.’³⁸

This was an advance on the article that had appeared in the same newspaper five months earlier. The ‘James Bond’ error was not repeated, although a new one was introduced—that the story was unpublished—and then contradicted. Two new locations were listed, Beirut and London, neither of which were in Cleary’s script.

The next piece of news came four days later, in one of Ian Fleming’s favourite newspapers, Jamaica’s Daily Gleaner. It was titled ‘Another Bond film’:

‘Of the making of James Bond films there seems to be no end. It has recently been announced that British novelist Kingsley Amis, an authority on the work of Ian Fleming, is to be special story and script consultant on “The Diamond Spy”, which George Willoughby is to make in association with Richard Todd’s independent company.

The film will be based upon a story outline which Fleming never completed. It was drafted after his investigations for the London Sunday Times into international diamond smuggling. The series of articles he wrote were later published in book form and entitled The Diamond Smugglers. The Diamond Spy, which is scheduled to cost about £1,500,000, will be filmed almost entirely on location in South Africa, Beirut, Amsterdam, the Baltic coast of The Federal Republic of Germany and London. It has not yet been announced who will play Bond.’³⁹

This is similar to the previous San Mateo Times piece, but Embassy and Anglo-Amalgamated have now been replaced by ‘Richard Todd’s independent company’ and we have another reference to an uncompleted story outline by Fleming. Canaway is not mentioned: in a letter to John Collard on 19 April 1966, Willoughby explained that he had fallen ill and been replaced by Robert Muller, who had completed his first draft that week. Muller was a former theatre and film critic who had written for the prestigious Armchair Theatre TV series in Britain; he later married the actress Billie Whitelaw. As with the outlines by Fleming and Amis and the work of Derry Quinn and Anthony Dawson, the whereabouts of his script are unknown.

On 14 March 1966, Boxoffice reported that Nat Cohen had left for New York the previous week for ‘a series of production discussions’ about four projected Anglo-Amalgamated films: an adaptation of Far From The Madding Crowd, slated to star Julie Christie; Rocket To The Moon, based on Jules Verne’s novel; Lock Up Your Daughters!, the Lionel Bart musical; and The Diamond Spy, ‘based on the Ian Fleming story’.⁴⁰ The other three films would all be produced and released within the next three years: only the Fleming project failed to make it onto celluloid.

Willoughby’s letter to Collard on 19 April had contained another oddity: instead of the usual ‘Willoughby Film Productions Limited’ heading, the letterhead now read ‘Cleon Productions Limited,’ and listed the company’s directors as Richard Todd and George W. Willoughby. The company was mentioned in another article in the San Mateo Times—evidently Willoughby’s preferred outlet for his press releases—in August 1966:

‘Film on Diamond Racketeers Being Made From Fleming Book

Robert Muller has been set to prepare the final screenplay of Joseph E Levine’s “The Diamond Spy”, the unpublished story by the late Ian Fleming, which will be bought to the screen by Levine’s Embassy Pictures in conjunction with Nat Cohen’s Cleon Productions Ltd.

The five-million-dollar co-production will be produced by George Willoughby, and is tentatively set to go before the color cameras late this year. The story of the smashing of a huge international band of diamond racketeers, it will be filmed in color on location in South Africa, Beirut, Amsterdam, West Germany and London.

Embassy Pictures will distribute the film worldwide, with the exception of the United Kingdom.’⁴¹

So it would appear that Nat Cohen had set up a new company with Willoughby and Todd, Cleon Productions. Perhaps it was a cheeky take on Eon, with Cohen and Levine’s initials added.

On June 7 1966, Willoughby wrote to Collard to invite him to a meeting at his offices with the director John Boorman, then just starting out on his career.⁴² But at this point, the correspondence and the newspaper articles dry up—it seems that Willoughby had finally run out of steam. Expectations for the project had changed: from the early idea that it should not try to emulate the James Bond films but have its own flavour, as time went on, the pressure had increased to make it more Bond-like. In a letter to John Collard on June 1 1966, Willoughby had said that the film’s distributors ‘equate Fleming with Bond and our difficulty is to strike a story line that has all the excitement that people expect from Fleming’s stories, without going into the ridiculous fantasy of the present Bond films’.⁴³

Shortly after this, it seems the project finally petered out, and The Diamond Smugglers went the way of countless other film projects—although not for want of trying. Kingsley Amis returned to writing novels, and a couple of years later was commissioned to write the first post-Fleming Bond adventure, which was published as Colonel Sun. Bob Parrish became one of the five directors to work on Charles Feldman’s Bond spoof Casino Royale, while John Boorman went on to direct the likes of Point Blank, Deliverance and The Tailor of Panama. Richard Todd continued his career as an actor on stage and screen until his death from cancer in December 2009.

Jon Cleary became a best-selling thriller-writer, penning a long-running series about a Sydney cop called Scobie Malone. The first novel in the series, The High Commissioner, was published in 1966. Malone is charged with arresting the Australian High Commissioner in London for murder, but finds he has to stop an assassination plot against the same man by a gang of Vietnamese terrorists. The character of Malone—tough but honest, laconic but empathetic—is not a million miles from Roy O’Brien. By the end of the novel, Malone has fallen in love with a young Dutch-born Australian girl called Lisa Pretorious, herself not dissimilar to Vicki Linden; they later marry. At one point in the novel Malone lets slip to Lisa that he is a civil servant, and she asks if he has a number, ‘like James Bond’.⁴⁴ The book was filmed in 1968 as Nobody Runs Forever, with Rod Taylor as Malone; Ralph Thomas directed.

According to Cleary, the death knell for The Diamond Smugglers was internal politics at Rank. ‘Rank liked my script,’ he says. ‘But then Earl St John, who was handling the project there, fell ill. A London lawyer whose name I forget [Michael Stanley-Evans] succeeded him, and his first step was to publicly announce that he was discontinuing all projects that had been started by St John.’

Cleary remained justifiably proud of his screenplay of The Diamond Smugglers: as well as being a gripping story, it has the DNA of Fleming’s book running through it, and is infused with both the intrigues of the diamond-smuggling business and the dramatic landscape of South Africa. It remains a fascinating what-if in cinema history, as we are left to wonder what impact it might have had if George Willoughby had succeeded in bringing it to cinema screens in the Sixties, and John Blaine had battled it out with James Bond at the box office.